Phillip M. Carter, Florida International University

When India invited delegates attending the G20 summit in September 2023 to dinner with “the President of Bharat,” rather than “the President of India,” it may have looked to the world like a simple case of postcolonial course correction.

The word “India” is, after all, an exonym – a placename given by outsiders. In this case, the name came from the British, who ruled the subcontinent from 1858 to 1947, a violent period of colonialism that later came to be called “the British Raj.”

“Bharat,” on the other hand, is the word for “India” in Hindi, by far the most spoken language in the nation. Alongside English, Hindi is one of two languages used in the Indian Constitution, with versions written in each language.

“Bharat” may, therefore, look like a well-reasoned and uncontroversial replacement for a term anointed long ago by outsiders – something akin to how Eswatini, Zimbabwe and Burkina Faso updated their countries’ names from the colonial designations “Swaziland,” “Rhodesia” and “Upper Volta,” respectively.

But the use of “Bharat” has elicited outcry from the political opposition, some Muslims, and Hindu conservatives in the south, reflecting ongoing tensions in India between language, religion and politics.

Two different language families

My book with fellow linguist Julie Tetel Andresen, “Languages in the World: How History, Culture, and Politics Shape Language,” covers the language history and politics of India.

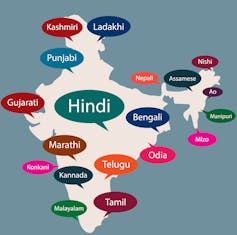

Hindi is the most-spoken language in India, but its use is largely relegated to a part of the country that linguists refer to as “the Hindi belt,” a massive region in northern, central and eastern India where Hindi is the official or primary language.

Around 1500 B.C.E., a group of outsiders from Central Asia – known now as the Indo-Aryans – began migrating and settling in what is now northern India. They spoke a language that would eventually become Sanskrit. As groups of these speakers separated from one another and spread out over northern India, their spoken Sanskrit changed over time, becoming distinctive.

Most of the languages spoken in northern India today – Hindi, Punjabi, Bengali and Gujarati, among many others – derive from this history.

But the Aryans were not the first group to inhabit the Indian subcontinent. Another group, the Dravidians, was already living in the region at the time of the Aryan migrations. They may have been the original inhabitants of the Indus-Valley Civilization in northern India. Over the millennia, the Dravidians migrated to the southern part of the subcontinent, while the Aryans fanned out across the north.

Today, Dravidians number about 250 million people. Dravidian languages, such as Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam, have no historical relationship and virtually no linguistic similarities to the Indo-Aryan languages of the north.

Dravidians spurn Hindi

By the time the Raj ended in 1947, English had been established as the language of the elites and was used in education and government. As the new nation of India took shape, Mahatma Gandhi advocated for a single Indian language to unite the diverse regions and for many years championed Hindi, which was already widely spoken in the north.

But after independence, opposition to Hindi grew in the Dravidian-speaking south, where English was the favored lingua franca. For Tamils and other Dravidian groups, Hindi was associated with the Brahmin caste, whom many felt marginalized Dravidian languages and culture.

For many people in the south, Hindi came to be seen as a language as foreign as English. To keep tensions from spilling over, the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, supported verbiage in the constitution adopted in 1950 allowing for the continued use of English in government for a limited period.

Violence nevertheless continued in the south for years around what was seen as the unfair promotion of Hindi. It abated only when Indira Gandhi – Nehru’s daughter and the third prime minister of India – pushed to codify English, alongside Hindi, as an official language in the constitution.

Today, the Indian Constitution recognizes 22 official languages.

Nationalists push for one official language

The Partition of India in 1947 – corresponding to the dissolution of the Raj – led to the creation of Pakistan, which was set up to aggregate the majority Muslim regions from the colonial state. An independent India was set up to include the majority non-Muslim regions.

Today, roughly 97% of Pakistan’s population is Muslim. In India, Hindus make up about 80% of the population, while Muslims make up about 14% – more than 200 million people.

This is where modern domestic politics come into play.

“Hindutva” is a brand of far-right Hindu nationalism that emerged in the 20th century in response to colonial rule but gained its biggest following under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janta Party, or the BJP.

As a political ideology, Hindu nationalism should be distinguished from Hinduism, a religion. It advances policies that seek to promote Hindu supremacy and are widely considered anti-Muslim.

One such policy is the promotion of Hindi as the sole official language of India. Speaking in 2022 at a Parliamentary Official Language Committee meeting, BJP Home Minister Amit Shah said, “When citizens of states speak other languages, communicate with each other, it should be in the language of India.”

To Shah, the “language of India” and Hindi were one and the same.

Suppressing Urdu

Muslims in India speak the languages of their communities – Hindi among them – as do Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Christians.

However, making Hindi the national language could be viewed as one part of a broader political project that can be characterized as anti-Muslim. That’s why the political opposition is against using “Bharat,” even though many Muslims are themselves Hindi speakers.

These politics become even clearer in the context of the BJP’s attempts to limit the use of Urdu – a language with a high degree of mutual intelligibility to Hindi – in Indian public life.

Although Urdu and Hindi are remarkably similar, their differences take on outsized religious and national significance.

Whereas Hindi is written in the Devanagari script, which has strong cultural associations with Hinduism, Urdu is written in the Perso-Arabic script, which has strong associations with Islam. Whereas Hindi draws on Sanskrit for new words, Urdu draws on Persian and Arabic, again emphasizing associations to Islam. And whereas Hindi predominates in India, Urdu is the official language of Pakistan, along with English.

Thus the appearance of “Bharat” in official government correspondence may reopen old wounds for Muslims – and even for conservative Hindus in the Dravidian-speaking south who might otherwise support Modi and the BJP.

Although an official name change is unlikely in the immediate future, “Bharat” will likely continue to serve as a rallying cry for right-wing nationalists.

To them, the conciliatory language politics of Nehru and Indira Gandhi are a thing of the past.

Phillip M. Carter, Professor of Linguistics and English, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.