Mike Conway, Indiana University

As election night approaches, Americans will turn to their televisions, computers and smartphones to watch results come in for local, state and national races. Over the years, news coverage of winners and losers has become must-watch programming – even if it is, as longtime NBC election-coverage producer Reuven Frank put it in 1991, “a TV show about adding.”

The main goal of journalists on election night was – and is – to be the first to correctly declare the winner. It’s an attitude driven by the public’s interest in quick results, supercharged by journalistic competition.

I have been studying journalism history for more than 20 years and before that worked in newsrooms on election night for almost as long. Through experience and research, I know the rush to announce a winner didn’t start with the internet – or television or radio, for that matter.

The public, especially the sector deeply interested in politics, has always wanted to know the results as soon as possible. Another standard of election night, at least in the past century, is that the journalists announce a winner in the presidential race well before all the votes are counted – and weeks before the results are formally certified.

Election night 2020 may be very different.

The spectacle of election night

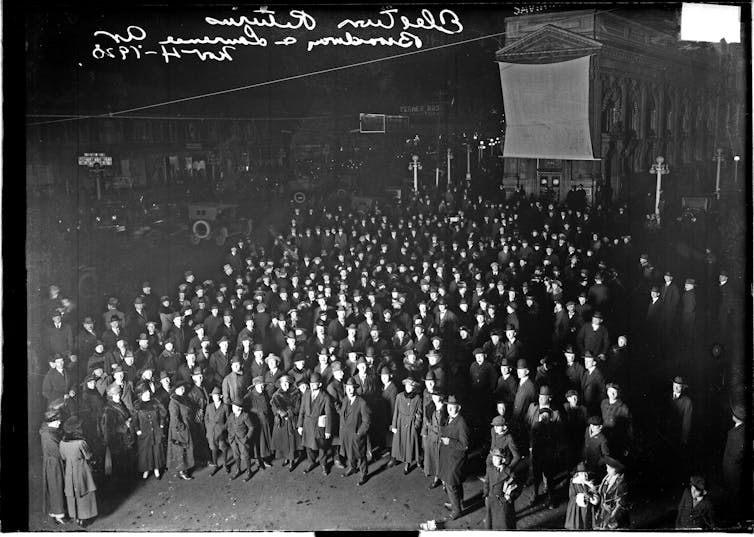

Starting in the late 1800s and continuing well into the next century, New York newspapers used a vast array of floodlights, magic lantern displays, stereopticon projections, and other dazzling visual pyrotechnics to announce results on election night.

In 1892, The New York Herald and the New York World newspapers, as well as the Chicago Herald, used a variety of lighting techniques to signify state and national results in incumbent President Benjamin Harrison’s race against former President Grover Cleveland. The New York Herald used a searchlight at Madison Square Garden and pointed it toward Brooklyn to announce Cleveland’s victory. While these effects were designed to announce the winner before the next edition of the paper, the visual displays also drew crowds, turning election night into an entertainment event.

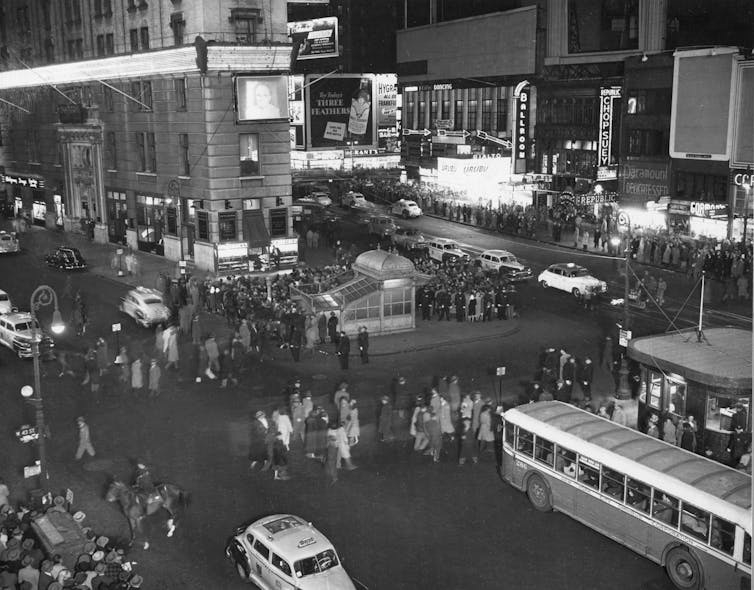

In 1904, when The New York Times moved its offices to a new location dubbed “Times Square,” the paper ramped up the election night spectacles and also added a ball drop on New Year’s Eve. In 1928, just in time for Herbert Hoover’s election, the Times unveiled the “zipper,” a lighted electronic sign with 4-foot-high scrolling letters that circled the building with the latest information.

Media historian Dale Cressman considered the quarter-million-dollar sign a combination of “newspaper promotion, competition, and the desire to be first.” For more than 30 years, the Times zipper displayed election night results and other major news stories.

Broadcasting the election results

Eight years before the Times zipper, newspapers in Detroit and Pittsburgh, as well as in other locations, took to the radio airwaves to announce Warren Harding’s election as president. By 1932, the radio networks relayed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s victory over incumbent Herbert Hoover to the more than 60% of American households that had radios.

After World War II, television took over the role of getting preliminary election results out to the public as quickly as possible.

Throughout the broadcast era, the television networks considered the political conventions and election nights as their most visible and important broadcasts every four years. They unveiled new equipment and visual imagery, graduating from writing numbers on a blackboard to lighted signs, and when color television finally caught on, using different colors to signify Republicans or Democrats. The networks also added computers and the latest prediction methods with the determination to announce the winner first, for ratings and bragging rights.

Since the networks were relying on prediction, and not the actual counted votes to determine the winner, the moment that came to symbolize the end of presidential election was the concession speech. That was especially true in such close elections as the one in 1948, when Harry Truman beat Thomas Dewey. In 1960 the telling moment came the day after Election Day, when Richard Nixon gave a concession speech, congratulating John F. Kennedy on his victory.

The networks used the speech to confirm their prediction, and the losing candidate used the speech to symbolize the peaceful acceptance of the public’s will, even though that act had no official role in determining the winner.

Speedy results

Throughout the rest of the 20th century, vote counting sped up while pollsters and other analysts came up with more intricate ways to predict the vote count.

This emphasis on speed without consequences culminated in 1980 when NBC News used exit polling to announce at 8:15 p.m. Eastern time that Ronald Reagan had defeated incumbent Jimmy Carter. NBC was roundly criticized for announcing a winner before all the nation’s polls had closed. Critics believed the network’s emphasis on being first may have hurt voter turnout on the West Coast.

In 1990, the top broadcast and cable TV outlets teamed up with The Associated Press to create the Voter News Service. The idea was that the collective effort would share the costs – and the results – of vote analysis on election night. The analysis combined exit polling, actual vote totals, voter turnout and other data to predict who would win. It also offered the possibility that a wide range of media outlets would be in sync, in terms of timing and the results themselves, as they announced predicted winners.

The confusion of 2000

The presidential race of 2000 became the election night when predictions and traditions failed the networks and the American public. The television networks had conditioned Americans to believe projections were as reliable as vote totals, and that a concession speech signaled the end of the race. In addition, because the networks all relied on the same data, they couldn’t catch problems with the predictions.

Using Voter News Service data, the networks first announced Vice President Al Gore had won Florida, but then changed to report Texas Gov. George W. Bush had won Florida, and therefore the whole election. Gore even made a private concession call to Bush, before calling back to rescind his concession.

In reality, the Florida vote was too close to call. But in many people’s minds, Bush had been declared the winner on television. It took a Supreme Court decision and a public Gore concession speech to cement Bush’s victory.

[Get our most insightful politics and election stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

A focus on vote counting

In 2002, the Voter News Service was disbanded, replaced the following year by the National Election Pool, which serves the same purpose. For 2020, The Associated Press and Fox News have left that consortium and will both be using the wire service’s own service, AP VoteCast.

The results may take hours, if not days or even weeks, to compile. That will make election night 2020 unlike any other in history. It’s my hope that the journalists and news organizations will resist their history of predicting a winner quickly, and instead focus on witnessing – and explaining – the process, however long it may take.

Mike Conway, Associate Professor of Journalism, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.