Erle C. Ellis, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and James Watson, The University of Queensland

Nature urgently needs our help. Wild creatures, from songbirds to butterflies and from primates to tortoises, are disappearing so rapidly that they could be lost forever together with the wild forests, grasslands and other habitats that long sustained them. We humans already use nearly half of all Earth’s land to sustain ourselves, and the most productive parts at that. Meanwhile, the habitats remaining for the rest of life are shrinking to levels too low to sustain themselves.

To ensure a future in which humanity thrives together with the rest of nature, people around the world will need to work together like never before.

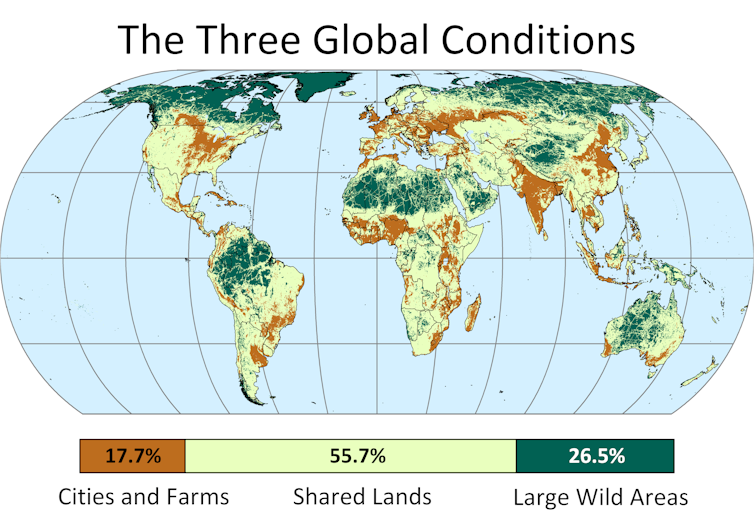

To help make this happen, our team of scientists and conservation experts have developed a new world map highlighting three conditions of landscapes across the planet that will need to be approached differently if we are to succeed in conserving biodiversity globally. These conditions are cities and farms, large wild areas and shared lands.

In a commentary accompanying our map, we argue that for too long, efforts to conserve nature globally have acted as if this entire planet is equally influenced by the human world. Yet different landscapes differ profoundly in how they are used and influenced by people, demanding different strategies to conserve biodiversity. Our map aims to clarify these conditions to enable people to work together to conserve biodiversity more fairly and equitably.

Biodiversity is our natural heritage

The extraordinary richness of life we’ve inherited is an irreplaceable treasure that makes the world an immeasurably better place for people. Biodiversity underpins many of the ecological functions that sustain us, from healthy soils to a stable climate, and provides a wide variety of benefits to human health – mental and physical.

Yet the ultimate value of our biodiverse natural heritage is beyond any economic measure. Wild nature is our lifeblood and our heritage, connecting us with each other and the rest of life on this planet.

The good news is that people have already begun to rise to the challenge. For example, international commitments now aim to protect 17% of Earth’s land. But it is widely agreed that these and other existing conservation efforts are not nearly strong enough to halt nature’s decline.

In October 2020, nations working together through the global Convention on Biological Diversity will meet in Kunming, China to negotiate more ambitious international targets for conserving nature across the planet. One of the bolder proposals is to develop international commitments to officially protect 30% of Earth’s land area by 2030, and 50% by 2050.

But for any bold conservation agenda to succeed, an unprecedented level of international commitment will be needed. Perhaps the greatest obstacle is the many profound differences in social, economic and natural conditions that persist around the world. Some nations remain rich in unprotected biodiversity and wild habitats but are much less developed economically. Some are the opposite.

So how can such different nations and regions join together to make shared commitments and investments to save nature across this entire planet?

Three conditions for conserving nature

The first step is to build a basic consensus that conserving biodiversity can benefit all people, as long we share the efforts fairly at every level, from backyards to biosphere reserves, and across every social, economic and natural context, from the densest of cities to the most remote wild areas. To succeed, strategies need to be suited to the many different types of landscapes to conserve.

Let’s start with the parts of the world where most of us live and most of our food comes from – the cities and farmlands that take up 18% of Earth’s land surface. These are not just full of people, crops and livestock, but also include some of the densest concentrations of vertebrate diversity on Earth, including many imperiled species of mammals and birds.

In these parts of the world, there needs to be widespread adoption of wildlife-friendly farming practices. Remnant and recovering habitats must be conserved within farmlands and agrichemical production reduced, even while increasing agricultural production. And even in the densest of cities, interconnecting small areas of protected habitat, such as parks and nature reserve networks, can successfully sustain some populations of highly endangered species. In the Indian city of Mumbai, for example, a national park conserves leopards.

Large wild areas, where human influences are lowest, including large parts of Amazonia and Canadian boreal forests, still cover about a quarter of Earth’s land. Here, an emphasis on large-scale protection, such as the Five Great Forests Initiative in Central America, will be the most effective strategy. To avoid damaging the last of Earth’s unaltered ecosystems, new infrastructure and land uses, including mining, should be limited as much as possible. Recognizing indigenous people’s rights to land, so they can conserve their own lands, can also be highly effective; a large proportion of large wild areas are indigenous-owned and managed lands.

Perhaps the greatest conservation opportunities of all may reside within the most common condition of Earth’s land today – shared landscapes. Though parts of these working landscapes are still used intensively for agriculture and settlements, most of their area is composed of remnant and recovering habitats and areas lightly used for extensive grazing and forestry.

Conservation in shared lands can include regional protected area networks, such as the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, community conservation reserves, and conservation-friendly farms and cities that prioritize the needs of local people. For example, the Lewa community conservancy in Kenya, which protects habitat for endangered black rhinos, includes programs to assist local farmers to maximize their production while minimizing any negative impacts to protected habitats.

Shared lands are also home to almost half of Earth’s indigenous sovereign lands, another reason why expanding and empowering indigenous land sovereignty is considered essential to global efforts to expand conservation.

Doing your part to save nature

Distant wildlands are critical habitat for so many species, but effective conservation also depends on efforts in our own neighborhoods and the regions where our food comes from.

Think of nature when making new friends, caring for family, shopping, working, casting your vote, or donating your time or money to make the world a better place. The challenges ahead are not small, but working together across our farms and cities, shared landscapes, and large wild areas, we can make the nature of our planet whole and healthy again.

Contributors to the creation of the Three Conditions map include Harvey Locke of the International Union for Conservation of Nature World Commission on Protected Areas, Oscar Venter of University of Northern British Columbia, Richard Schuster of Carleton University, Keping Ma of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiaoli Shen of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Stephen Woodley, IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, Naomi Kingston and Nina Bhola of the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Bernardo B. N. Strassburg of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica and International Institute for Sustainability in Brazil, Axel Paulsch of the Institute for Biodiversity in Regensburg, Germany and Brooke Williams, University of Queensland.

Erle Ellis is a member of the American Association of Geographers The association is a funding partner of The Conversation US.

Erle C. Ellis, Professor of Geography and Environmental Systems, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.